One of the more difficult texts in the New Testament has been what Paul says (or rather, does not say) concerning slaves in the Greco-Roman era. Past interpreters of the Bible, for example, are puzzled by Paul’s lack of explicit injunctions against slavery in his Letter to Philemon. Why does Paul not exhort Philemon to emancipate the slave Onesimus who has recently converted to Christianity? Why leave room or ambiguity in his letter, so that centuries later, white Southerners during the Civil War era can misinterpret what Paul says to Philemon and claim:

- The Bible’s defense of slavery is very plain. St. Paul was inspired, and knew the will of the Lord Jesus Christ, and was only intent on obeying it. And who are we, that in our modern wisdom presume to set aside the Word of God… and invent for our selves a higher law than those holy Scriptures?… Paul sent back a fugitive slave [Onesimus], after the slave’s hopeful conversion, to his Christian master [Philemon] again, and assigns as his reason for doing that master’s right to the services of his slave — John Hopkins (1864), an Episcopal pastor (excerpt taken from Swartley, Slavery, Sabbath, War and Women, 1983)

There are many reasons why Hopkins above makes a horrific misreading of Paul. But let me start by saying that Paul, in my opinion, is quite explicit when he states:

- 15 For perhaps on account of this he [Onesimus] was separated (from you – Philemon) for the hour, in order that you might receive him as a receipt paid in full eternally — 16 no longer as a slave, but above a slave, a beloved brother, very (beloved) to me, but how much more (beloved) to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord. (Philemon 1:15-16; Eng. trans. my own)

When Paul says to Philemon to receive Onesimus back not as a slave but as a “beloved brother (ἀδελφὸν ἀγαπητόν)… in the flesh and in the Lord (ἐν σαρκὶ καὶ ἐν κυρίῳ),” what does he mean by ἐν σαρκὶ (v. 16)? I know what “a brother in the Lord” is (i.e., a fellow Christian believer), but what is a “brother in the flesh”? I think ἐν σαρκὶ καὶ ἐν κυρίῳ points to the heart of Paul’s message: to let Onesimus’ new found status as a Christian brother be reflected in his social status in the real world. If Onesimus is a “brother in the Lord,” then make him a “brother in the flesh” as well: free him. A “brother in the flesh” is a freed Christian whose emancipation in the Greco-Roman world is a natural theological outworking of his identity as a member of God’s family. Otherwise, Paul need not have included the phrase ἐν σαρκί.

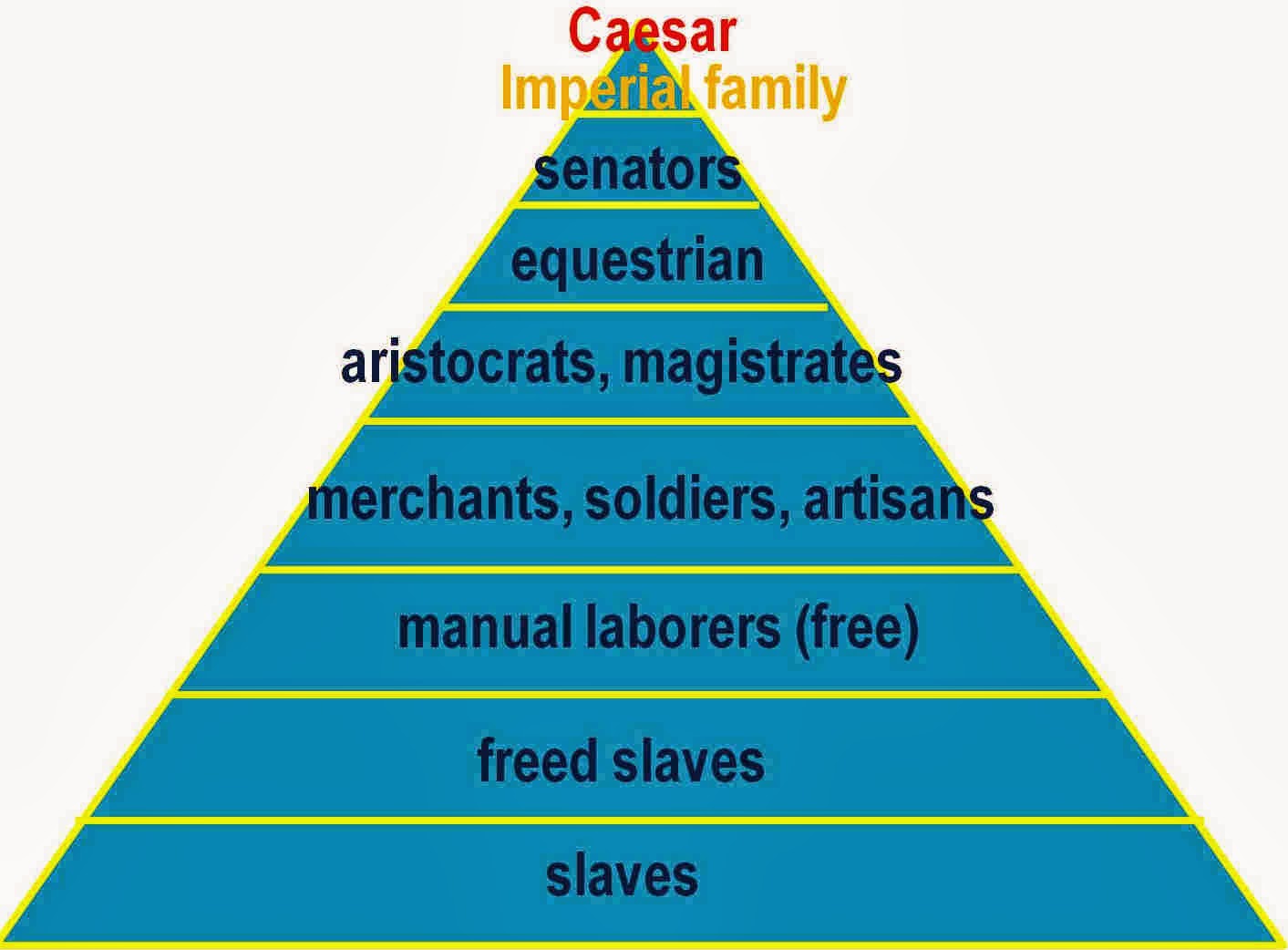

So why does not Paul simply say: “Emancipate Onesimus! Free him!”? To quote Lloyd Lewis: “his [Paul’s] ambiguity [over emancipation] may not be so much a matter of his indecision as his unwillingness to canonize the social roles found in his environment” (Stony the Road We Trod, 246). If Paul simply said, “emancipate Onesimus,” Onesimus’ newfound status as a freed slave would only be one step above the bottom rung of Greco-Roman society. The freed slave is not at the same social level as that of a free person, as the diagram below indicates.

|

| © 2014 Max Lee |

Above is a diagram of the Patronage Pyramid (a good introduction to how the patronage-client system works in the ancient world can be found in Richard Saller, Personal Patronage under the Early Empire, 1982; David deSilva, Honor, Patronage, Kinship and Purity, 2000; or the more recent and technical treatment by John Nicols, Civic Patronage in the Roman Empire, 2014).

Notice that freed slaves are just above (unfreed) slaves but socially still below everyone else. Free persons were a higher and separate class but even among free people there was a very wide spectrum of privilege and position: some were manual laborers, others merchants, still others were magistrates, and even fewer were nobility who occupied the upper echelons of the Roman Empire .

Did Paul simply want to make Onesimus a freed person, canonizing Onesimus’ social role for his time and ours, or did Paul have something much grander in mind?

A freed person would still require help from his former master to make a jumpstart in life. The freed person, just emancipated, would require a patron who could sponsor, write letters of recommendation, and provide the initial resources or raw materials to open a new business. The freed person would become entangled in a web of financial and personal obligation under the patronage-client system and never be truly free. At the festivals and banquets, when people sat by social class, the freed person could never recline and eat at the same table of his former master.

In contrast, only in the church were slaves treated as fellow brothers and sisters in Christ. The church was called to think creatively about how our new identity as members of God’s family can be reflected in our social relationships in the wider world. Making Onesimus a freed slave would be too easy. Philemon was challenged by Paul to do more. Yes, emancipate Onesimus (make him a brother in the flesh), but more importantly treat your former slave as a brother in the Lord, beloved, for whom Christ died (1 Cor 6:20). Slave and free persons would share the same table and break the same bread at the Lord’s Supper. Their communion would be nothing short of a revolution in a world where the privileged stayed on top of the pyramid at the expense of the masses.

The church was called to flip the patronage pyramid over on its heels and turn the world upside down with the Gospel. The good news is that in Christ a former Diaspora Jew (Paul), a wealthy patron (Philemon) and a freed slave (Onesimus) can be called brothers and share a common identity as members of God’s family, paradoxically serving one another as “a slave of all” (πάντων δοῦλος; Mark 10:42; cf. 1 Cor 9:19).

Postscript 06/13/14: Exegetical Exercise: 1) Read the above post. 2) Go to the bible dictionaries/encyclopedias in the reference section of the university library and learn more about slaves/slavery in the Greco-Roman world (in Greek doulos/δοῦλος). 4) Interpret 1 Cor 7:20-23 drawing insight from your background study. In other words: how does understanding the status and function of slaves in the Greco-Roman world help you to understand Paul’s message/exhortations in 1 Cor 7:20-23? 4) Be sure to consult at least one academic commentary on your biblical text from the reference section.

You must be logged in to post a comment.