One of the best exhibits at the Getty Villa was the display of mummy masks from Roman Egypt. The use of portaits painted on the head of a mummy is a combination of Egyptian burial customs and Roman individualized portraiture traditions. Often wood panels are used for the portrait and later inserted into the mummy’s linen wrappings. Pigments were suspended in bee’s wax and brushes used to paint the face of the dead onto the panel. Sometimes a hardening agent like eggs yolk was applied.

Besides the excellent example of the mummy mask shown in my previous post, here are some of the other mummy portraits on display at the Villa (forgive some glares; I did my best to try to get a clean photo through the protective glass of the display):

|

| Portrait of a Roman-Egyptian Man (AD 200-25) Cropped hairstyle reflects the Severan era Photo by Max Lee © 2015 |

|

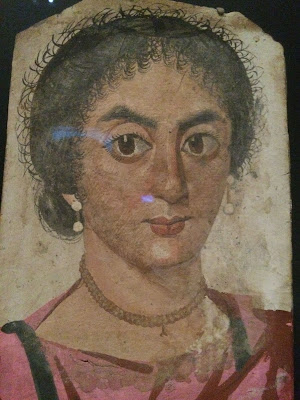

| Portrait of an Roman-Egyptian Woman (AD 170-200) Dress, jewelry, and hairstyle depict a matriarch of wealth Photo by Max Lee © 2015 |

|

| Portrait of a Roman Egyptian Man (AD 200-50) holding a glass of wine and garland of flowers which are typically associated with funeral rites Photo by Max Lee © 2015 |

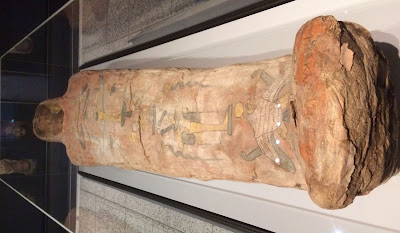

Rarely does one find a perfectly preserved mummy in antiquity, but the Getta Villa has one on display which shows nicely how the wood panel portraits like above were inserted in the wrappings of the mummy. Below is the mummy of the Roman Egyptian Herakleides (AD 50-100):

|

| Mummy Body of the Roman Egyptian Herakleides (AD 50-100) Photo by Max Lee © 2015 |

|

| Photo shows how the mummy portrait panel was inserted in the wrappings and the body itself was decorated further with symbols of protection and rebirth Photo by Max Lee © 2015 |

We are not exactly sure why the Egyptians created headmasks (often gold) which later evolved into the Roman practice of life-like portraits on wood panels inserted on top of the head coverings. But it may be that the spirit of the person was believed to be wandering around during the day and in order to return to its body at night, the portrait was there to help the human spirit recognize its own body.

Also worth noting is how the name of the man was written in Greek just above the feet. It’s hard to see but you can make out ΗΡΑΚΛΕ[ΙΔΗΣ] if you stare at the photo below:

I find the exhibit utterly fascinating for the example of cultural assimilation that has taken place among Egyptian religious practices. The portraits are ethnic Egyptians but these Egyptians are dressed like Romans! The names are spelled out in Greek. The ancient Mediterranean world was far more cosmopolitan than we might initially suspect, and the influence of Rome affected even the burial rites of the colonized population.

But there is another reason why I wanted to see this exhibit. Sometimes, instead of linen, strips of papyri were used with glue to make the cartonnage, or the cardboard-like materials created from plastering the mummy wrappings, much like children who make crafts from paper-mâché. Sometimes, the papyri they use are recycled from written texts and scrolls. The trick, then, is how to peel away the layers of paper-mâché papyri from the mummy mask or body and recover the written texts they contain. For New Testament scholars, much ado has been made about the possibility of a Gospel of Mark fragment discovered in a mummy mask (yet to be verified by the way!). More on this in the next post. For now, enjoy the photos from an incredible exhibit at Getty.

Text reads "מחטי שרך ד קח", probably to protect mummy feets.

Really? Pardon the pun, but it looks all Greek to me. 🙂 Are you talking about the text where it starts to fade? The left 1st letter looks like a "H" (ēta) rather than a ח (chē) to me and the rest of the letters look like the Greek letters as I have in the post.

Hmmm? It certainly gives me something to think about. Also, if you're right, the museum display is also incorrect. The Getty has it as a Greek inscription. In any case, thanks Toni for your post! Really appreciate your taking the time to comment and add to the discussion. Blessings! Max